Early on, before the Transatlantic Slave Trade exploded on the scene, Latin America and eventually, North America utilized forms of forced labor similar to feudalism and indentured servitude. Latin America initially attempted to exploit the natives in a system of indentured servitude while claiming to do the good work of Christianizing the natives. The encomienda system resulted in Latin American natives bound to land given to Spanish conquistadors by the Spanish crown. The encomienda system permitted “the right to derive income and labor from specified indigenous communities.” 1 In Colonial America, colonists incorporated a system of indentured servitude as white people came from Europe, sometimes by choice, sometimes by force, to work in the new land. T.H. Breen describes that in the 1600s, Virginia, for example, needed “a large inexpensive labor force, workers who could perform the tedious tasks necessary to bring tobacco to the market.”2 Ultimately, both Latin America and Colonial American needed what they considered a more reliable, less expensive option than indentured servitude. Enter African slavery. Religious groups such as the Puritans and the Quakers still sought to Christianize indigenous people while enslaving the natives. (The Quakers, however, eventually became one of the initial groups to manumit their slaves and fought diligently towards the earliest abolition movements.)

While both Latin America and Colonial America built fortunes on the backs of slaves, conditions and experiences for their slaves differed in several ways. In his book From Rebellion to Revolution, Eugene Genovese explained that in Latin America, hundreds of slaves worked vast plantations away from their masters/plantation owners, creating an absentee relationship between slaves and owners. In North America, it was more likely to see 20 or so slaves working smaller plantations and living on the plantation, near the masters/owners, allowing for a relationship to ensue — be it a positive or negative one. Slaves in North America had it a little better when it came to food and necessities versus their counterparts in Latin America, where famine ran rampant, and masters provided their slaves very small portions, often forcing the slaves to grow their own food when time permitted. Slave life was grueling in both societies, but research and study show much harsher conditions and experiences in Latin America. Slaves in Latin America worked day and night and essentially were worked to death in many cases. Large populations of slaves in poor, abysmal conditions also meant epidemics of disease, thereby wiping out significant numbers of slaves.

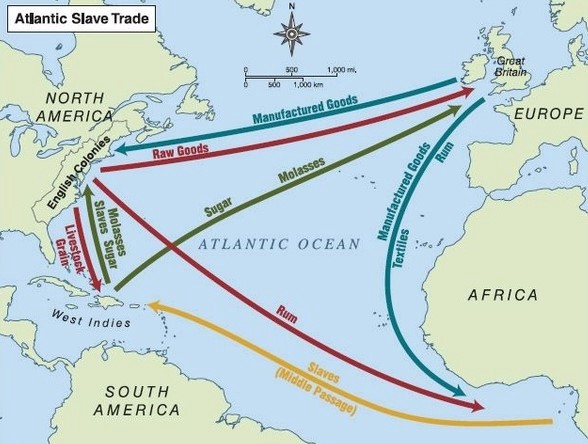

In Latin America, female slaves were fewer, and therefore, lower birth rates occurred. There was a continuous influx of new slaves arriving in Latin America to replace the dead, sick, and elderly slaves. Slavery was so widespread and heavily utilized in Latin America that the “Sugar Islands” in particular became a “sea of slavery.” 3 Latin American slave masters quickly replaced sick, elderly, and dead slaves. African slaves greatly outnumbered wealthy white European plantation owners. Slaves in North America often received permission to marry and reproduce, thus “growing” an American-born slave population. Slaves in North America established a more cohesive sense of community. Female slaves worked as servants and in the fields. Slaves in North America, because of the “closer” relationship they had with their masters, found influence in the culture and religion of their masters. They sometimes went to church with the masters and their families, and many knew the Bible.

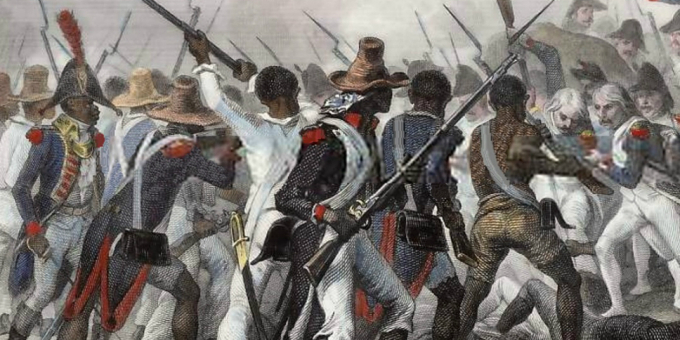

We know that in America, racism raged throughout, especially in the South. Laws related to slaves were stricter in North America versus Latin America. The geographical differences in terrain also made escape more difficult in North America as opposed to Latin America. Rebellions and revolts held significant differences. While slave revolts occurred in America, they emerged as more of a rowdy rumbling, and whites easily subdued the rumblings. The uprisings did not elicit the response or hold the magnitude of those revolts in Latin America. In Latin America, the revolts took on a more revolutionary shape and scope, as in the case of the Haitian Revolution. In America, slaves appeared to be more reserved, acquiesced in a sense, biding their time while large-scale and violent revolution occurred in Latin America.

Slavery is ugly and reprehensible no matter where it occurs geographically. (And, yes, it still appears in present-day, around the world.) Too often, people respond to the topic of slavery in three ways: they fully condemn it, no questions asked, no further discussion; they explain it away; or they ignore it, shutting themselves off to further education. It is not our job to excuse nor condemn slavery, but as historians, it is our job to analyze and understand how and why it happened. In general, we all must learn from mistakes throughout history. Still, we cannot fully appreciate this learning without studying and understanding what happened, where and when, and why/how it happened. We must be careful not to lump slavery into one distinct category.

Citations:

1Robert L. Paquette, and Mark Michael Smith. The Oxford Handbook of Slavery in the Americas. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2016), 70.

2T.H. Breen. “A Changing Labor Force and Race Relations in Virginia 1660-1710.” Journal of Social History 7, no. 1 (1973): 4.

Sources:

Breen, T. H. “A Changing Labor Force and Race Relations in Virginia 1660-1710.” Journal of Social History 7, no. 1 (1973): 3–25.

Genovese, Eugene D. From Rebellion to Revolution: Afro-American Slave Revolts in the Making of the Modern World. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State Univ. Press, 2006.

Paquette, Robert L., and Mark Michael Smith. The Oxford Handbook of Slavery in the Americas. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2016.