When thinking about the steel and iron production industry in postbellum America, thoughts typically go immediate to the city of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Andrew Carnegie. Pittsburgh is often referred to as the “Steel City” because of the enormous role it played in the Industrial Age of America. The man who built the Steel City was Gilded Age titan Andrew Carnegie. Carnegie’s story is one of rags to riches, a Scottish immigrant who tinkered around in various occupations before the realization that steel served as the foundation, the crown jewel, and base element to success in postbellum America as industrialization flourished. The shifting economy in the United States from farming and agriculture began blazing towards manufacturing and industrialization. “Demand for huge quantities of steel was voracious because steel proved to be a superior, and increasingly cheaper, basic material with myriad uses in industrial America.”[1] Essentially, he who controlled the steel industry, ruled the industry and all the massive contracts related to steel production – bridge-building and railroads especially. “Thus, by 1901 capitalists, engineers, and workers had created revolutionary technological advances in the Pennsylvania steel industry.”[2] It is important to remember that the North already established itself in manufacturing and expanding in industrialism. Conversely, the Civil War decimated the South, which relied heavily on agriculture. For the South to establish itself in a larger industrial and manufacturing arena, Birmingham was built from the ground up into such a city.

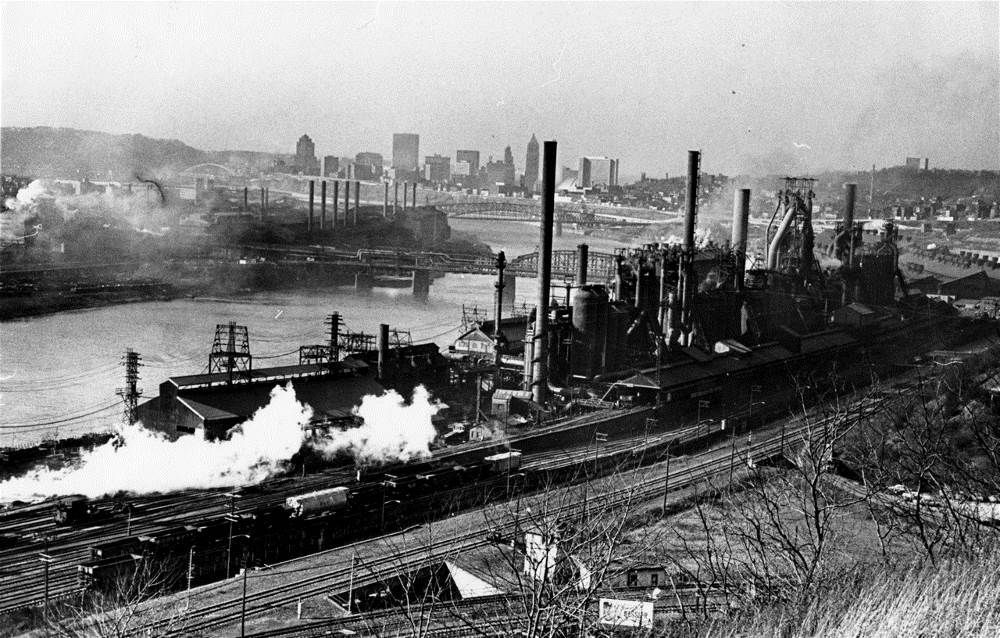

Pittsburgh communities grew into steel empires. Andrew Carnegie purchased the Edgar Thomason Works in the Braddock section of Pittsburgh in 1875. The Homestead Works’ largest plant opened in 1883 and became a massive operation. Workers often lived in poorly constructed housing villages right behind the plant. The living conditions were deplorable and lacked indoor plumbing. Pittsburgh winters were brutally cold, and the houses offered little warmth. Pittsburgh summers proved unbearable at times as the extreme urbanization of the landscape gave no reprieve from the heat of the weather nor the heat from the furnaces and equipment of the plant.

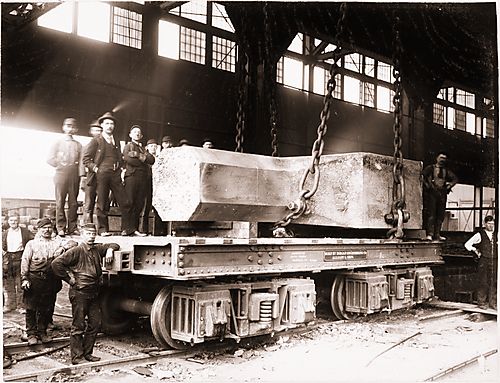

Steelwork in Pittsburgh was grueling work. Steelworkers often worked seven days a week, often in twelve-hour shifts under dangerous conditions. The wages barely totaled $2.50 per day. According to the U.S. Labor Statistics Bureau, daily wages in Pennsylvania steel plants varied among skilled and unskilled workers. In 1885, for example, daily wages ranged from $1.65 per day to $5.35 per day, depending on job assignment and skill level.[3] Most of the Pittsburgh steelworkers were immigrants from Ireland, Wales, and Scotland.

A significant shift from agriculture to manufacturing in the South was also emerging. In 1870, the city of Birmingham, Alabama, became a vital industrial city thanks to its rich supplies of iron ore, limestone, and coal – the essential components in producing iron and steel. The man primarily associated with thrusting Birmingham into the steel industry was a merchant and railroad worker, Colonel James Withers Sloss. Sloss may not have amassed the notoriety and popularity that Andrew Carnegie gained, but he helped establish Birmingham into a thriving industrial city. By 1879, Birmingham opened its first successful iron furnace, and by 1880, Birmingham stood as Alabama’s largest iron furnace. The booming industry led to a boom in population as well, elevating Alabama to the fourth-highest iron-producing state in the United States.

Many southerners, especially African Americans, fled the rural agricultural South for Birmingham. The African American influx into Birmingham was facilitated by those seeking better opportunities in industry versus agriculture, especially those entangled in sharecropping. Segregation existed with the African American workers, often through assignments into the lower-paying, more demanding jobs. By 1890, Birmingham also drew large numbers of immigrants from Germany, Italy, Russia, and Greece. Like the steelworkers of Pittsburgh, the workers in Birmingham faced exhausting work in horrific and dangerous conditions. The living conditions were also similar to those in Pittsburgh, rickety housing behind the plant, constructed into a miniature town. Often the workers in Birmingham received tokens to exchange at the company store instead of actual wages.

Despite the differences in size and scope of their empires and the steel cities they built, both Sloss and Carnegie were men who knew how to seize upon the entrepreneurial opportunities resulting from the circumstances of time and place, as discussed by Randall Holcombe. The entrepreneurial success for Sloss and Carnegie, though different in many ways, held a similar feature. They recognized an opportunity – one that “requires specific knowledge of time and place.”[4] In their own ways and in their own structure, both Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Birmingham, Alabama contributed a rich history to the making of industrial America.

Bibliography:

Dabbs, B.L.H. “Homestead Steel Works 1893-1895.” Historic Pittsburgh – University of Pittsburgh Library System. Carnegie Museum of Art. Accessed January 17, 2022. https://historicpittsburgh.org/islandora/object/pitt%3A1999.19.8.

Dabbs, B.L.H. “Homestead Steel Works 1893-1895.” Historic Pittsburgh. University of Pittsburgh Library System – Carnegie Museum of Art. Accessed January 17, 2022. https://historicpittsburgh.org/islandora/object/pitt%3A1999.19.20.

Holcombe, Randall G. “Progress and Entrepreneurship.” The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics. Vol 6, No. 3. (Fall 2003): 3-26.

Novack, David E., and Richard Perlman. “The Structure of Wages in the American Iron and Steel Industry, 1860-1890.” The Journal of Economic History 22, no. 3 (1962): 334–47.

Sisson, William. “A Revolution in Steel: Mass Production in Pennsylvania, 1867-1901.” IA. The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archeology 18, no. 1/2 (1992): 79–93.

White, Langdon. “The Iron and Steel Industry of the Birmingham, Alabama, District.” Economic Geography 4, no. 4 (1928): 349–65.

Wright, Gavin. “The Economic Revolution in the American South.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 1, no. 1 (1987): 161–78.

[1] William Sisson. “A Revolution in Steel: Mass Production in Pennsylvania, 1867-1901.” IA. The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archeology 18, no. 1/2 (1992): 79.

[2] Ibid, 92.

[3] David E. Novack, and Richard Perlman. “The Structure of Wages in the American Iron and Steel Industry, 1860-1890.” The Journal of Economic History 22, no. 3 (1962): 342. Novack and Perlman include a detailed table of statistics from 1860-1890, citing the following for their source: U.S. Labor Statistics Bureau, History of Wages in the United States from Colonial Times to 1928. Bulletin No. 604 (Washington D.C.: Govt. Printing Office, 1934), pp. 241-50.

[4] Randall G. Holcombe. “Progress and Entrepreneurship.” The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics. Vol 6, No. 3. (Fall 2003): 13.