‘T WAS mercy brought me from my pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there’s a God–that there’s a Saviour too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye—

‘Their color is a diabolic dye.’

Remember, Christians, Negroes black as Cain

May be refined, and join the angelic train.

~ Phillis Wheatley, On Being Brought from Africa to America[1]

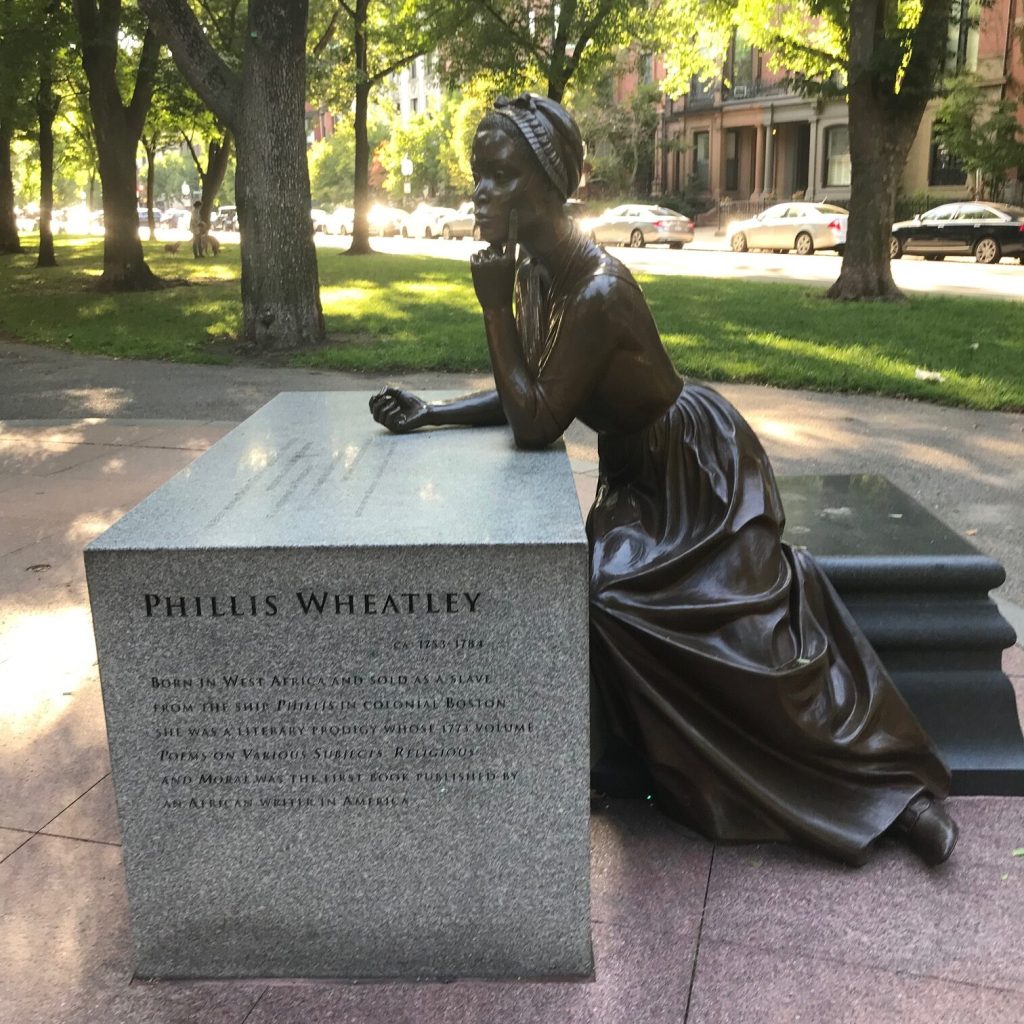

Phillis Wheatley was born in Gambia in West Africa and came to Colonial America in 1761, sold into slavery at the tender age of seven. She arrived in Boston, frail of frame and cloaked in little more than a filthy rug. Prominent businessman, John Wheatley, purchased Phillis to serve as a domestic servant to his wife, Susanna. We know very little about her life in Africa. According to Geo W. Light, “We cannot know at how early a period she was beguiled from the hut of her mother; or how long a time elapsed between her abduction from her first home and her being transferred to the abode of her benevolent mistress, where she must have felt like one awaking from a fearful dream.”[2]

Despite living in enslavement, Phillis escaped a hardened, violent life of back-breaking labor. The Wheatley Family, in many ways, treated her as one of their own, serving as a family structure versus a slave/master. The Wheatley Family saw early on that Phillis was bright, and they began educating her, teaching her to read and write. Light stated, “We gather from her writings, that she was acquainted with astronomy, ancient and modern geography, and ancient history; and that she was well versed in the scriptures of the Old and New Testament.”[3] She was not only a voracious reader but a talented writer. Somewhere around the age of 12-14, she began writing poetry. Despite being a sickly child plagued by asthma, Phillis kept to her studies.

In 1773, she went to London with Nathaniel Wheatley (the son of her master/mistress) to publish her first collection of poems, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. This book became the first book written by a black woman in Colonial America. Phillis was proof that a black person, moreover a black woman, would be intelligent, well-read, and a talented artist capable of incredible writing and poetry. Wheatley wrote beautiful, eloquent poetry and was published in Colonial America and England. Delighted by a poem Phillis wrote for him, George Washington praised Wheatley’s writing.

Phillis Wheatley found tremendous inspiration for her poetry and writing through the Bible and Eighteenth-Century evangelical Christianity. Living during the First Great Awakening, she was especially captivated by the preaching of George Whitefield. She published a poem in 1770, On the Death of the Rev’d Mr. George Whitefield, wherein she wrote:

“we Americans revere

Thy name, and mingle in thy grief sincere

New England deeply feels, the orphans mourn,

Their more than father will no more return.”[4]

Phillis also spoke up about slavery and abolition, pointing out the irony of the desire for Colonial America’s desire for independence from England. In a letter to Mohegan Indian Presbyterian minister and missionary, Samson Occum in February 1774, Phillis spoke to the concept of “the glorious dispensation of civil and religious Liberty,” for all, tying it to the Israelites and their struggle for freedom from Egyptian slavery. Wheatley wrote, “This I desire not for their Hurt, but to convince them of the strange Absurdity of their Conduct whose Words and Actions are so diametrically opposite.”[5]

Phillis received manumission in early 1774, shortly before her mistress, Susanna, passed. With the passing of Mr. and Mrs. Wheatley and their daughter, Mary, and with the son, Nathaniel relocating to England, Phillis found herself alone. Eventually, she married John Peters in 1778, a free black man with lofty ambitions but a sketchy work history. The difficulty for free black men to compete for jobs, especially good jobs, mattered little for John Peters because he lacked a strong work ethic. Phillis had to work to help support them. According to Light, “In an evil hour he was accepted; and he proved utterly unworthy of the distinguished woman who honored him by her alliance.”[6]

Success in life, especially in her writing, seemed to elude Phillis Wheatley. With her poor health and loathsome, lazy husband, Phillis lost the chance to advance in a career with writing. Phillis died alone in 1784; her husband was incarcerated due to mounting unpaid debt. Phillis Wheatley was unlike most female slaves, for she was treated with kindness and given a good life while simultaneously receiving a valuable education. The master-slave relationship, therefore, differs considerably compared to most slaves. Phillis Wheatley escaped grueling labor and abuse. In her adult life, especially during her marriage, she never received the protection and family structure she experienced growing up with the Wheatley Family. Phillis was essentially alone. Despite all the sadness and loss she endured and a life cut tragically short, Phillis Wheatley’s legacy is that of a remarkable and talented woman who wrote from the heart.

Bibliography:

Catherine A. Brekus. “Contested Words: History, America, Religion.” The William and Mary Quarterly 75, no. 1 (2018): 3-36.

Levernier, James A. “Phillis Wheatley (ca. 1753–1784).” Legacy 13, no. 1 (1996): 65-75.

Light, Geo W. “Phillis Wheatley, 1753-1784. Margaretta Matilda Odell. Memoir and Poems of Phillis Wheatley, a Native African and a Slave. Dedicated to the Friends of the Africans.” North American Slave Narrative Database. University of North Carolina Chapel Hill. https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/wheatley/wheatley.html.

Seeber, Edward D. “Phillis Wheatley.” The Journal of Negro History 24, no. 3 (1939): 259-62.

Letter from Phillis Wheatley to Reverend Samson Occom. 11 February 1774 [electronic edition] “Africans in America/Part 2/Letter to Rev. Samson Occum.” PBS – Africans in America / Part 2. Public Broadcasting Service. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2h19.html.

[1] Geo W. Light. “Phillis Wheatley, 1753-1784. Margaretta Matilda Odell. Memoir and Poems of Phillis Wheatley, a Native African and a Slave. Dedicated to the Friends of the Africans.” North American Slave Narrative Database. University of North Carolina Chapel Hill. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/wheatley/wheatley.html.

[2] Ibid, 10-11.

[3] Ibid, 17.

[4] Geo W. Light. “Phillis Wheatley, 1753-1784. Margaretta Matilda Odell. Memoir and Poems of Phillis Wheatley, a Native African and a Slave. Dedicated to the Friends of the Africans.” North American Slave Narrative Database. University of North Carolina Chapel Hill. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/wheatley/wheatley.html.

[5] Letter from Phillis Wheatley to Reverend Samson Occom. PBS – Africans in America / Part 2. Public Broadcasting Service. Accessed April 18, 2021. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2h19.html.

[6] Geo W. Light. “Phillis Wheatley, 1753-1784. Margaretta Matilda Odell. Memoir and Poems of Phillis Wheatley, a Native African and a Slave. Dedicated to the Friends of the Africans.” North American Slave Narrative Database. University of North Carolina Chapel Hill. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/wheatley/wheatley.html.