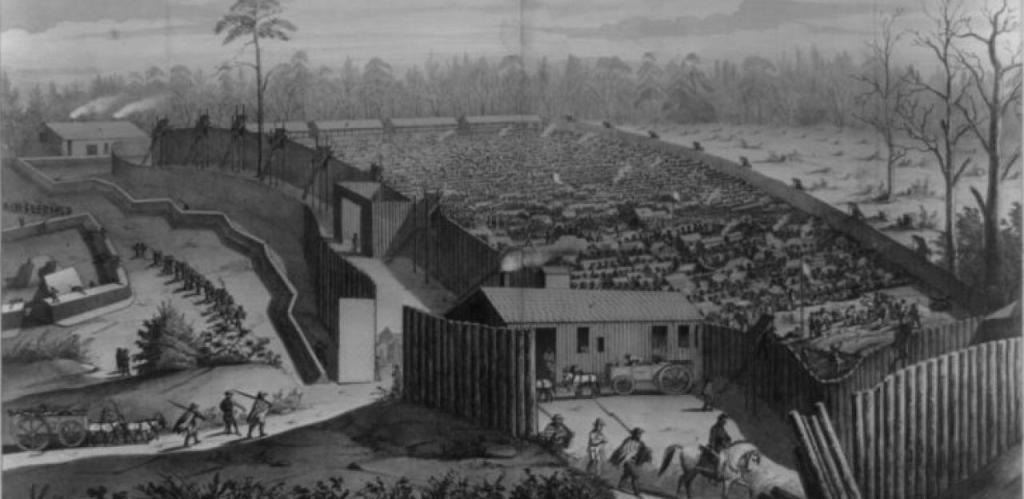

Historians estimate that fifty-six thousand Civil War soldiers died as prisoners of war. That figure fails to include soldiers who perished shortly after their liberation, unable to recover from their hellish incarceration. Scholarship on Civil War prisons encompasses an intriguing and chaotic historiography. Numerous memoirs, journals, official government documents, and newspapers revealed prisoners’ dreadful experiences. Scholarship exists on individual and more famous prisons like Andersonville, Elmira, Camp Douglas, and Libby Prison. As with a lot of topics of the American Civil War, studies often ooze with finger-pointing between the North and the South. To begin sorting through the topic, one must take a step back and consider an important question one nurse in Richmond asked upon seeing liberated Union soldiers from Andersonville, “Can any pen or pencil do justice to those squalid pictures of famine and desolation?”[1]

Civil War prisons and the treatment of Civil War prisoners of war appear somewhat elusive throughout history books, even though four hundred thousand soldiers found themselves incarcerated in enemy prison camps. Of the estimated one hundred fifty prison camps established during the war, most only reveal a plaque or historical marker mentioning their existence. Perhaps the absolute darkness of the subject causes historians to shy away from it. Americans treated fellow Americans horribly, making it a challenging topic to discuss. After all, the atrocities committed in the prison camps occurred here in the United States between the Confederate and Union sides versus a foreign enemy from a faraway land.

When looking at the Civil War prison camps, their complexity emerges. Perhaps that is why no comprehensive list and overall study on each camp exists. How do historians forge a comprehensive study of the prisons that includes the key people involved in the policies of prisons? How do historians begin to add to the topic’s historiography while avoiding polemics and finger-pointing? Too often, the unpleasant nature of darker chapters in American history remains in the shadows. Civil War prisons are indeed dark; however, historians are responsible for bringing light to the darkness. Both sides in the American Civil War hold responsibility for the prisons. In sorting through the tangled web of questions, how do historians begin to answer them? Researching the topic through political, military, social, and cultural history methodologies reveals the story behind the prisons.

Significant, accessible research exists in primary and secondary sources — from the Official Records of the War of the Rebellion to newspaper articles, diaries/memoirs of soldiers (both published and unpublished), and official papers. Secondary sources appear plentiful, but it is rare to find comprehensive studies on the prisons. The first substantial study on Civil War prisons appeared in 1930 with William Best Hesseltine’s book, Civil War Prisons. Hesseltine examined the conditions within prisons like Andersonville and Libby Prison and concluded that the horrific conditions emerged from “war psychosis” and a campaign by Northern newspapers to shock readers by exaggerating the conditions and treatment by guards. According to Hesseltine, “The close of the war, the surrender of the Confederate forces, the release of the prisoners North and South did not mark the end of the psychosis which had been engendered in the mind of the people during the conflict.”[2] Historians on the topic give Hesseltine a nod for pioneering the topic. In 2005, Sanders wrote While in the Hands of the Enemy, which sparked controversy as Sanders assigned blame from the top down – beginning with Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis and down to commandants at each prison. Sanders surpassed Hesseltine’s war psychosis and dug deeper to reveal the blame belonged to both sides of the war. His work serves as an invitation for more research to expand the historiography.

To research the topic thoroughly, historians must ask various questions. How and where the camps did the camps start? When and where did they evolve versus devolve? Why were some camps more notorious than others? Where does the responsibility fall regarding the conditions of the camps and the treatment of prisoners of war? How did the dissolution of the Dix-Hill Cartel affect Civil War prisons and conditions? Why should historians focus on this topic and keep the memory of the camps and prisoners alive? Does a comprehensive list of prisoner-of-war camps exist? Why is the topic important?

It is often said that the American Civil War has been over-studied. Many historians disagree. Are there elements of the War or methodologies that have received more research and scholarship? Yes. However, numerous topics continue to be under-mentioned and studied too little. Civil War prisons and prisoners of war embody that sentiment. The background related to those questions posed above and their answers requires a balanced research approach and multiple methodologies. Military and political history prove crucial, but social and cultural history must also coalesce to best understand Civil War prison camps and prisoners of war. The combination allows for examining the cruel and unusual punishment and experiences those men endured in the camps while revealing more details on the camps in totality. That combination ignites a more thorough study into why some camps are well-known while others vanished from history with little more than a historical marker to tell their story. As with most history topics, one answer or explanation rarely exists. Moreover, to fully understand a historical topic, more than one methodological approach provides a better, more well-rounded narrative, especially regarding dark and complicated topics.

Bibliography:

Hesseltine, William Best. Civil War Prisons. Kent OH: Kent State University Press, 1973.

Pember, Phoebe Yates. A Southern Woman’s Story: Life in Confederate Richmond. St. Simons Island GA, GA: Mockingbird Books, 1890.

Sanders, Charles W. While in the Hands of the Enemy: Military Prisons of the Civil War. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2005.

[1] Phoebe Yates Pember. A Southern Woman’s Story: Life in Confederate Richmond. (St. Simons Island, GA: Mockingbird Books, 1890) 55.

[2] William Best Hesseltine. Civil War Prisons: A Study in War Psychology. (Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University Press, 1930), 233.