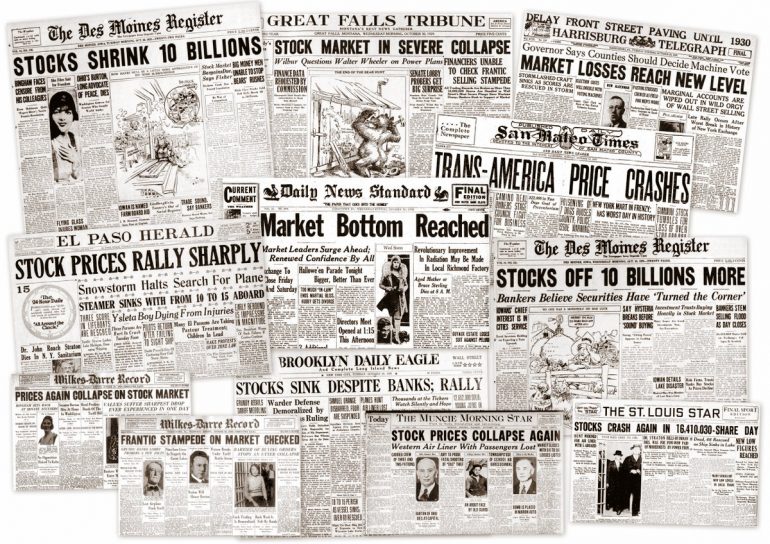

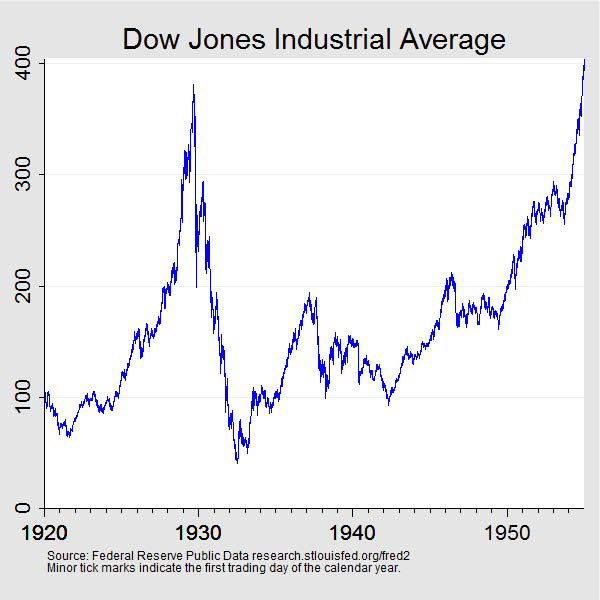

Americans watched in horror in late October 1929, as the Stock Market tumbled then calmly rebounded before crashing completely on Black Tuesday, October 29, 1929. For five days, the market wobbled erratically as investors watched helplessly, beginning on Tuesday, October 24, 1929. Life was about to change drastically for millions of Americans. Before we look at the thoughts and theories related to both the Wall Street Crash and eventually the Great Depression, we must look back to truly understand America’s conditions and everyday life.

One decade earlier, it was post-World War I. America, unlike the European countries, was thriving. Victorious from World War I and escaping Europe’s utter devastation, Americans frolicked in peace and economic prosperity. Items like cars and appliances, once considered luxury items, were now bought by anyone. Heavy spending abounded. Installment buying and buying on credit became all the rage. The practice of buy now, pay later allowed so many to upgrade their lifestyles. Towns expanded, electricity lit up cities and towns, and consumer consumption skyrocketed.

Life was good. Throughout World War I, Liberty Bonds inspired a culture of investment and promoted investment ventures for so many Americans. In the 1920s, brokerage offices spawned, bringing investment opportunities beyond government bonds to promote corporate stocks. After all, investing was viewed as a safe practice; the Liberty Bonds proved it, right? Investing spread beyond the wealthy and elite city folk. Anyone could strike it rich as average Americans caught the spirit of entrepreneurship through stockbrokers and Wall Street. It was common to buy on margin – a credit system that allowed borrowing vast amounts on credit while brokerage firms covered the rest. According to Eugene N. White, “This eagerness to buy stocks was then fueled by an expansion of credit in the form of brokers’ loans that encouraged investors to become dangerously leveraged.”[1]

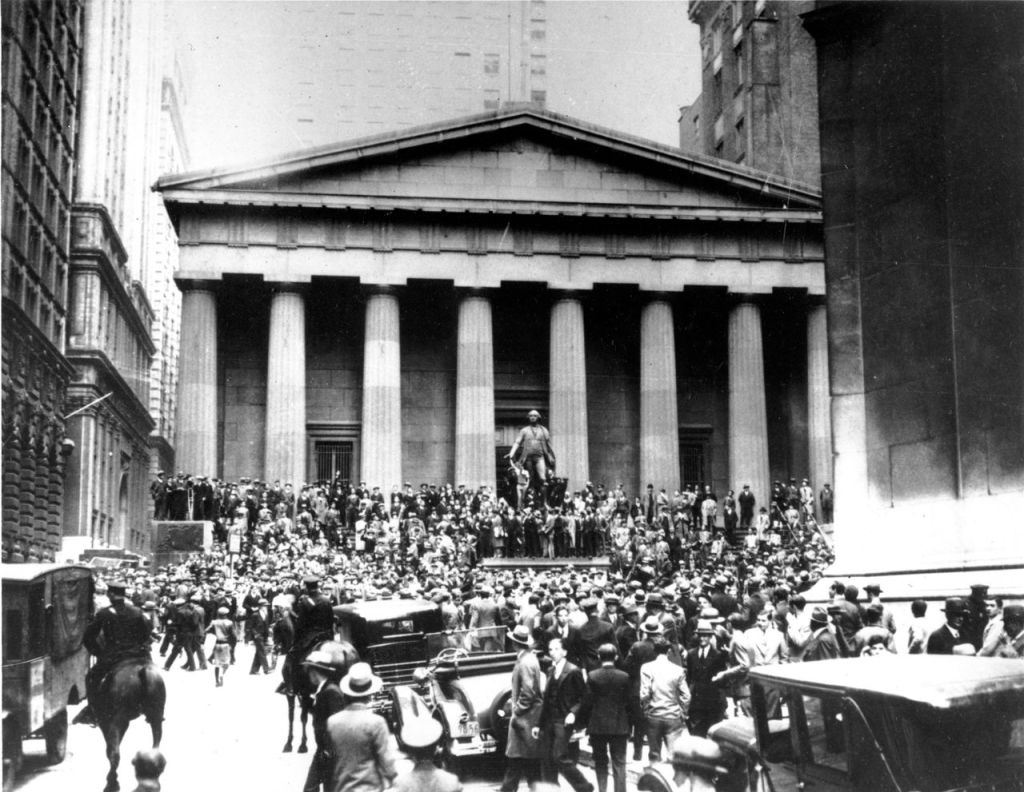

In reality, the Stock Market operated with a sense of lawlessness, corruption and experienced minimal government oversight. It was unregulated, an easily rigged system that proved simple to manipulate. The successes of buying and selling started to appear too good to be true. People ignored the cautionary warnings and continued to invest. During the spring and summer of 1929, the stock market continued expanding, constantly increasing, brewing some suspicion. Feelings of uneasiness emerged, and the volatility of the market soon festered. On October 23, 1929, millions of shares were sold, and on Black Thursday, October 24, 1929, the beginning of the end came. A crash appeared inevitable as shock and panic at the downward spiral in the stock market erupted. Order and confidence declined as quickly as stocks dropped.

By Friday, October 25, a sense of calm set in as crisis as averted, or so it seemed. The weekend passed, and by Monday, October 28, the easy credit stocks – the buying with borrowed money ended in catastrophe. People who could not pay faced threats by brokers of selling their stocks. People scrambled, but disaster lurked, and on Tuesday, October 29, 1929, shares plummeted as relentless selling of stocks resulted in the market collapse and crash.

Billions of personal wealth disappeared in those five days in October 1929. Many people lost everything. The victims were not just investors. Over the next couple of years, the American economy bled into chaos, with banks closing. As word of bank closures spread, people ran to yank their own money out of banks. Ben S. Bernanke states, “The U.S. system historically suffered also from a more malign source of bank failures; name, financial panics.”[2] Companies felt the stranglehold of economic chaos, and massive layoffs across the country occurred. Businesses melted into financial crisis, with many closures. People could not get loans; businesses could not obtain credit to pay their workers. Gone were the spending sprees as demands sharply dwindled. “In the business sector, the incidence of financial distress was very uneven.”[3]

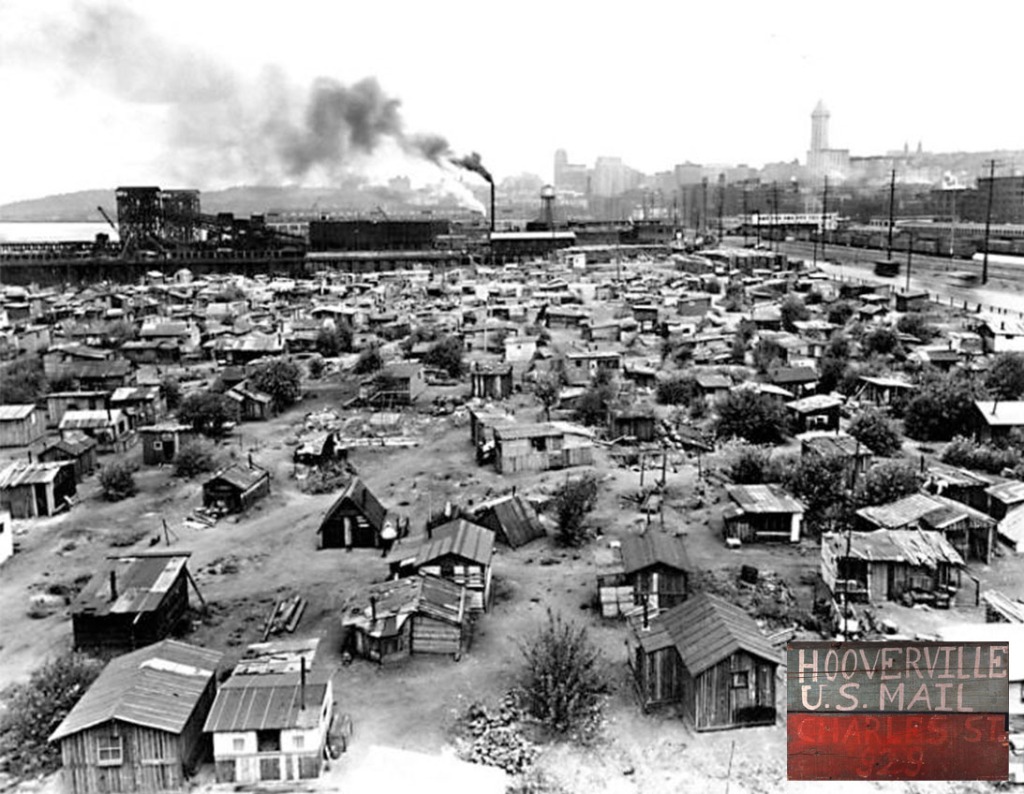

Poverty and homelessness skyrocketed as “Hoovervilles” sprung up around the country. Hopelessness and despair permeated America. The American government reeled in horror as blame shifted towards the administration. Everything appeared normal and acceptable before the crash, so the government allowed business as usual. With the presidential election of 1932 creeping up, America needed a hero, someone to end the financial and economic nightmare. Enter Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

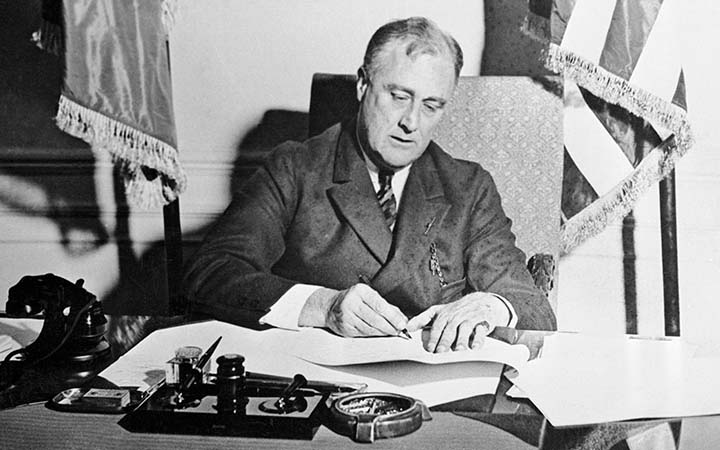

Franklin D. Roosevelt arrived at a time when many countries throughout the world drifted towards and became entangled in Communism, Fascism, and Nazism with a fevered hatred for capitalism. America would not falter towards a socialist and totalitarian system of government, and FDR was determined to restore the economy and restore the faith and confidence of the American people. FDR established the Securities and Exchange Commission. In his Fireside Chat of March 12, 1933, FDR stated:

“We had a bad banking situation. Some of our bankers had shown themselves either incompetent or dishonest in their handling of the people’s funds. They had used the money entrusted to them in speculations and unwise loans. This was of course not true in the vast majority of our banks but it was true in enough of them to shock the people for a time into a sense of insecurity and to put them into a frame of mind where they did not differentiate, but seemed to assume that the acts of a comparative few had tainted them all. It was the Government’s job to straighten out this situation and do it as quickly as possible — and the job is being performed.”[4]

FDR also worked tirelessly on the New Deal, which included: the regulation and supervision of the stock market, banking, and investing; specific laws for banks; added government supervision; and a major investigation into the Stock Market Crash. In May 1933, FDR thanked Americans for their patience and faith with the efforts, reminding them that the work continues:

“Throughout the depression you have been patient. You have granted us wide powers, you have encouraged us with a wide-spread approval of our purposes. Every ounce of strength and every resource at our command we have devoted to the end of justifying your confidence. We are encouraged to believe that a wise and sensible beginning has been made. In the present spirit of mutual confidence and mutual encouragement we go forward.”[5]

Bernanke notes, “Although the government’s actions set the financial system on its way back to health, recovery was neither rapid nor complete.”[6] The New Deal included various relief efforts for Americans. Price Fishback notes, “The lion’s share of New Deal grant spending from 1933 through 1939 was distributed under four major types of programs. Roughly half went to relief grants, about 20 percent went to public works, about 20 percent went to payments to veterans, and 10 percent was distributed to farmers.”[7]

While the New Deal and FDR’s efforts resulted in some economic bounce-back for the nation, ultimately, World War II ended the Great Depression and propelled the country towards economic vitality. Discussion and debate still exist in the theories over the causes for the Stock Market Crash of 1929. White notes, “Although most historians believe that the 1920s bull market was a bubble and concede only a small role for real factors, some contemporary observers attributed most of the market’s rise to fundamentals.”[8] As are most topics in history, the causes and effects of the Stock Market Crash and Great Depression and the results of the New Deal will continue to receive debate and discussion. As a final note, it is important to mention that I am no economist and hold no business background. As questions arise, I cannot say with certainty which theory I embrace on this topic. I am, however, a historian, and I believe strongly in understanding past events so as not to repeat the same mistakes.

Bibliography:

Ayres, Clarence E. “The Impact of the Great Depression on Economic Thinking.” The American Economic Review 36, no. 2 (1946): 112–25.

Bernanke, Ben S. “Nonmonetary Effects of the Financial Crisis in the Propagation of the Great Depression.” The American Economic Review 73, no. 3 (1983): 257–76.

Bernanke, Ben S. “The Macroeconomics of the Great Depression: A Comparative Approach.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 27, no. 1 (1995): 1–28.

Fishback, Price. “The Newest on the New Deal.” Essays in Economic & Business History Vol. 36 (2018): 1-23.

Higgs, Robert. “Crisis, Bigger Government, and Ideological Change: Two Hypotheses on the Ratchet Phenomenon.” Explorations in Economic History, Volume 22, Issue 1, (1985): Pages 1-28.

Romer, Christina D. “What Ended the Great Depression?” The Journal of Economic History 52, no. 4 (1992): 757–84.

Roosevelt, Franklin D. “On the Bank Crisis.” On the Bank Crisis – March 12, 1933. Franklin D. Roosevelt Fireside Chats. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum. Accessed December February 9, 2022. http://docs.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/031233.html.

Roosevelt, Franklin D. “Outlining the New Deal Program.” Outlining the New Deal Program – Mary 7, 1933. Franklin D. Roosevelt Fireside Chats. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum. Accessed December February 9, 2022. http://docs.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/050733.html

White, Eugene N. “The Stock Market Boom and Crash of 1929 Revisited.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 4, no. 2 (1990): 67–83.

[1] Eugene N. White. “The Stock Market Boom and Crash of 1929 Revisited.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 4, no. 2 (1990): 68.

[2] Ben S. Bernanke. “Nonmonetary Effects of the Financial Crisis in the Propagation of the Great Depression.” The American Economic Review 73, no. 3 (1983): 259.

[3] Ibid, 260.

[4] Franklin D. Roosevelt. “On the Bank Crisis.” On the Bank Crisis – March 12, 1933. Franklin D. Roosevelt Fireside Chats. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum. Accessed December February 9, 2022. http://docs.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/031233.html.

[5] Franklin D. Roosevelt. “Outlining the New Deal Program.” Outlining the New Deal Program – Mary 7, 1933. Franklin D. Roosevelt Fireside Chats. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum. Accessed December February 9, 2022. http://docs.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/050733.html

[6] Ben S. Bernanke. “Nonmonetary Effects of the Financial Crisis in the Propagation of the Great Depression.” The American Economic Review 73, no. 3 (1983): 272.

[7] Price Fishback. “The Newest on the New Deal.” Essays in Economic & Business History Vol. 36 (2018): 3.

[8] Eugene N. White. “The Stock Market Boom and Crash of 1929 Revisited.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 4, no. 2 (1990): 72.